On April 11, 2020, Parliament passed Bill C-14, also known as COVID-19 Emergency Response Act, No. 2. The main item in Bill C-14 is the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (“CEWS”) which grants employers who meet specific criteria the ability to recover up to 75% of wage costs incurred during the period of March 15 to June 6, 2020 [1]. While we can all applaud our parliamentarians from all political parties for their diligence and collaboration over Easter weekend, there are many issues with the CEWS that remain unaddressed. This paper identifies the main issues with the CEWS, details the implications of those issues and provides recommendations to potentially rectify them.

Details of the CEWS

Before we can discuss the issues with the CEWS, it is important to understand how it works. Even before we can describe how it works, it is equally as important to understand its intent. In its Backgrounder which was most recently modified on April 11, 2020 [2], the Government of Canada states the following:

This wage subsidy aims to prevent further job losses, encourage employers to re-hire workers previously laid off as a result of COVID-19, and help better position Canadian companies and other employers to more easily resume normal operations following the crisis. While the Government has designed the proposed wage subsidy to provide generous and timely financial support to employers, it has done so with the expectation that employers will do their part by using the subsidy in a manner that supports the health and well-being of their employees.

Therefore, and as expected, the intent of the CEWS is to provide financial assistance to employers and their employees negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. On this basis, we can confidently state that an outcome that either does not fairly assist those in need or, conversely, results in some entities being financially better off than they would have been absent the pandemic is not in keeping with the intent of the legislation.

In terms of eligibility, the definition of an eligible entity is quite broad and includes individuals, taxable corporations, partnerships, not-for-profits and registered charities. Thus, it appears that only public bodies (e.g. crown corporations) and certain non-taxable corporations are ineligible. There are currently 3 qualifying periods (i.e. the periods where a subsidy is available) which are:

- March 15 to April 11, 2020;

- April 12 to May 9, 2020; and,

- May 10 to June 6, 2020

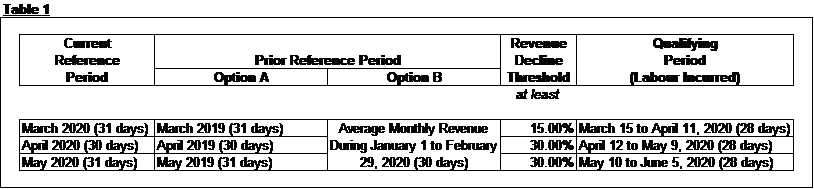

In order to be considered a qualifying entity, the employer will need to have qualifying revenues [3] during the current reference periods which have declined by a rate at least equal to specified percentages. There are restrictions under the computation of revenue heading which, as expected, requires employers to be consistent in their revenue recognition policy for purposes of measuring the decline in revenue. The specified percentages are 15% for March 2020 and 30% for each of April 2020 and May 2020. There is flexibility regarding base period selection for purposes of measuring the period specific declines in revenue, which are referred to as the prior reference periods. Essentially, entities can compare to either the corresponding month from 2019, or to average monthly revenue during January and February 2020. Table 1 below presents a summary of the rules regarding period selection and revenue decline thresholds:

Regarding the amount of the subsidy, there is a distinction between the treatment of employees and owners (and their family members). For employees, the subsidy is calculated as the greater of:

- The lesser of:

- 75% of eligible remuneration actually paid; and

- $847 per week.

- The lesser of:

- Eligible remuneration actually paid;

- 75% of baseline remuneration paid; and,

- $847 per week.

Essentially, the amount of benefit cannot exceed $847 per week in any case and the employer has the ability to recover 100% of eligible remuneration actually paid if said amount is no more than 75% of baseline remuneration paid. Baseline remuneration is defined as average weekly eligible remuneration paid during January 1 to March 15, 2020. For an owner (and their family members), only part 2) above applies, such that there needs to be a pre-existing pattern of qualifying remuneration in order to receive a subsidy.

Now that the basic mechanics of the CEWS have been explained, we can now discuss the main issues.

Issue #1: Causation

Surprisingly, there does not appear to be any requirement for the decline in revenue to be caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Stated otherwise, the presumption is that if entities have sustained a decline of revenue of at least 30% in say April 2020 relative to April 2019, that decline is attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Take, for example, an entity in the oil and gas sector. As of current date, the price of Western Canadian Select is around $7.50/barrel [4]. This compares to approximately $50.00/barrel in April 2019, which represents a decrease of approximately 85%. Therefore, a business in this sector may be eligible for the wage subsidy even though revenue volumes (i.e. barrels sold) have remained consistent from April 2019 to April 2020. Yes, it could be argued that the decrease in oil prices is partially attributable to a lack of demand associated with the COVID-19 pandemic; however, there are other factors at play as well such as the Saudi Arabia and Russia price war. To the extent the price decrease is principally associated with any non COVID-19 factors, any available wage subsidy is arguably not in keeping with the intent of the CEWS.

Conversely, the mechanics of the calculation offer limited assistance to newer entities, especially those with seasonal revenues. For example, a new restaurant which opened in July 2019 does not have a corresponding prior reference period from 2019 (i.e. March to May 2019) and, therefore, the prior reference period is limited to the average monthly revenue from January to February 2020. For many restaurants, especially those in seasonal tourist areas, revenues in January and February are very low or perhaps even non-existent. Accordingly, the revenue decline caused by the COVID-10 pandemic is not fully captured using the “before-and-after” approach mandated in the legislation.

One of the requirements to be considered a qualifying entity is that the individual who has principal responsibility for the financial activities of the eligible entity attests that the application is complete and accurate in all materials respects. In order to avoid entities obtaining a wage subsidy where the revenue decline is caused by non COVID-19 factors, the attestation statement should also require this individual to attest that, to the best of their knowledge, the decline in revenue is principally caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. More flexibility should also be granted to entities whose revenues have not declined by at least the minimum percentage as compared to the prior reference period but have in fact declined by more than the threshold relative to what would have been generated “but for” the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, a new business should not be bound to the January to February 2020 base period if they operate in a seasonal industry.

Issue #2: The Subsidy is not “Income Tested”

For some entities, their cost of labour relative to their pre-labour contribution margin is such that even with a 30% decline in revenue, the subsidization of labour results in them being better off as a result of the subsidy. For example, let’s assume an automotive repair business spends one third or 33.33% of their revenue on labour and another 33.33% on parts (the remaining 33.33% goes towards fixed costs and net income) and that both labour and parts are variable costs. If this entity realizes a decline in revenue of somewhere between 30% (i.e. the minimum threshold) and less than 50% and there is a corresponding decrease in labour, the wage subsidy, combined with the natural labour savings associated with less sales, more than offsets the lost pre-labour contribution margin [5] (this assumes that fixed expenses are unchanged). Since the entity has decreased labour costs at a rate consistent with the decline in revenue, the entity has not tried to continue to employ their workforce at the same level that existed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has presumably resulted in layoffs. Stated otherwise, this employer did nothing to support the employees it laid-off as it already recovered its continuing labour through actual revenue. Surely this result is not in keeping with the intent of the legislation.

In order to limit entities from benefiting from the wage subsidy, a solution would be to have the amount of the subsidy income tested. Stated otherwise, the subsidy should be further limited to the lesser of the amount of the subsidy determined by the existing formula, or the net change to net income.

Issue #3: Disregard for Increased Operating Costs

Entities can experience a loss of income due to a loss of revenue or an increase in operating costs (or both of these factors). As the subsidy is only triggered by a decline in revenue, there is no relief for entities who have lost income due to an increase in operating costs. Take, for example, a seafood processor who has increased employee pay in order to retain their workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic. Assuming revenue has continued as normal, there is no financial relief for this entity even though the loss of income may be the same as other firms that are receiving relief due do a decline in revenue.

A solution would be to expand the legislation to allow entities to obtain a subsidy for increased operating costs, but only if the decrease in net income caused by the increase in costs exceeds a prescribed percent of anticipated net income (i.e. similar to the 30% threshold for revenue), and the increase is principally tied to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Issue #4: Shareholder Remuneration

The definition of eligible remuneration does not include dividends, which is problematic for many self-employed corporate owners. Further, the formula specific to self-employed corporate owners (and their family members) limits the recovery to 75% of baseline remuneration (i.e. average weekly T4 income during January 1 to March 15, 2020). Thus, unless the corporate owner has paid himself/herself a regular salary (and not a dividend) during the 8 weeks ended March 15, 2020, the prospect of a wage subsidy regarding their own labour is severely limited. Yes, this type of corporate owner may be eligible for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (“CERB”) [6] instead, however, that benefit is limited to $500/week whereas the CEWS benefit is limited to $847/week. It seems unreasonable that a self-employed corporate owner should receive 40% less in financial aid just because he/she decided to receive dividends as opposed to salary [7].

A solution would be to include dividends within the definition of eligible remuneration or allow self-employed corporate owners the ability to receive a higher CERB limited to the CEWS maximum of $847/week, to the extent the loss of their available income meets that threshold.

Issue #5: Business Interruption Insurance

The legislation is silent with respect to the receipt of business interruption proceeds in the event the entity in question is covered for a loss of income due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Some may argue that if the entity in question receives insurance proceeds, said amount is already reflected in current reference period revenue and, therefore, the “before-and-after” comparison of prior reference period to current reference period revenue self-adjusts to limit a double recovery. However, if the entity’s insurance claim is not resolved until well after the qualifying period, the receipt of insurance proceeds and the corresponding accounting entry to record said “revenue” may fall outside of the period of analysis and, as such, it will not be adjusted for in the revenue decline formula.

Further, business interruption proceeds are generally measured and paid net of saved expenses and, therefore, the amount of proceeds recorded is not an apples-to-apples comparison of lost revenue. For example, assume that a furniture store which has a contribution margin of 50% has lost 60% of its revenue during a qualifying period, which results in a loss of income amounting to 30% of projected revenue [8] (i.e. 50% x 60%). If the business interruption proceeds are then recorded as actual revenue during the qualifying period, there will still be a revenue decline of 30%; however, net income has been full restored to its projected normal state. It would be unreasonable for this business to also receive a subsidy just because of the mechanics of the formula.

The presence of both the CEWS and business interruption proceeds presents an interesting chicken-or-egg quantum discussion for both insurers and the federal government. Does business interruption reduce CEWS or the other way around?

In order to prevent a scenario resulting in a double recovery, the definition of qualifying revenue should be expanded to include the implied revenue value in any business interruption proceeds, even if the proceeds are received after the qualifying period.

Conclusion

According to the program Backgrounder [9], the CEWS is expected to cost $73 billion and represents more than 70% of the total cost of direct government support measures currently being offered. While the CEWS will undoubtedly provide much needed assistance, there are material issues with it which, left unaddressed, can result in some being left out in the cold and others better off as a result of receiving it. Modifications to the current legislation are required to limit the possibility of these unintended outcomes and to provide Canadians with a better return on their investment.

The statements or comments contained within this article are based on the author’s own knowledge and experience and do not necessarily represent those of the firm, other partners, our clients, or other business partners.

- Also known as the qualifying period, which may also be extended for a prescribed period beyond June 6, 2020 that ends no later than September 30, 2020

- Qualifying revenue is defined to exclude extraordinary items and the computation require entities to be consistent in their revenue recognition policy for the purpose of measuring the decline.

- We discuss the potential benefit in more detail in our article entitled “Unintended Consequences: Will The CEWS Make Company Profits Higher Than Normal?” This example also assumes that the recovery is not limited by having any per employee wages in excess of $847 per week.

- The intent of Canada’s integrated tax system is to prevent a scenario where dividends are financially more attractive than salary, or vice versa.

- In this instance, projected revenue is synonymous with prior reference period revenue.