It has now been thirteen years since the Ontario Arthur Wishart (Franchise Disclosure) Act, 2000, SO 2000 [1], was enacted. The Act, named after Arthur Wishart, a Conservative MPP who championed the rights of franchisees in the 1970’s and 1980’s, is designed to protect the often unsophisticated purchasers of franchises by “redressing the imbalance of power” [2] as between franchisor and franchisee that is typically inherentpng in such transactions.

The Act does so by requiring, except in certain exempted situations, that franchisors provide to prospective franchisees a disclosure document containing particular prescribed information that was felt by the Legislature to assist a franchisee in deciding whether or not to purchase a franchise from the franchisor. This disclosure document must contain all “material facts” about the franchise including particular “material facts” prescribed by regulation, financial statements of the franchisor, copies of all agreements the prospective franchisee will be asked to sign, certain mandatory statements, and also other information and documents as prescribed by regulation [3].

Not only are franchisors required to disclose all “material facts”, with the definition of that phrase under the Act appearing to have been deliberately left vague so as to require franchisors to disclose an extremely wide variety of information [4], but the regulations to the Act lay out a veritable laundry list of information that must be included in any franchisor’s disclosure package.

The Act then gives teeth to this disclosure obligation by providing franchisees with a time-limited, private law right to rescind their franchise agreement if they were either never given this disclosure, or if the disclosure they were given did not meet the informational requirements of the Act. As part of this rescission right, the Act includes a section (subsection 6(6)) that defines specific financial obligations with which a franchisor must comply when a franchisee rescinds its franchise agreement. Generally speaking, the obligations in subsection 6(6) are to reimburse the franchisee all the money they injected into, or lost while operating, the franchise. This ensures the franchisee is restored to its pre-franchise position.

Over the thirteen years since the Act was proclaimed in force, relatively few reported legal decisions have dealt with quantification under subsection 6(6). Primarily because of this lack of jurisprudential interpretation, but also due to its wording, subsection 6(6) still raises many questions in terms of how it is to be applied, on the part of both franchisees and franchisors.

Furthermore, the wording of the Act does not exactly parallel how franchise businesses are operated, leaving gaps between the intent of the Act to restore franchisees to their pre-franchise position, and the categories of the Act that define the amounts to be paid to franchisees. These gaps may over- or under-compensate franchisees who make subsection 6(6) claims.

This article will explore the subsection 6(6) rescission remedy, both from an accounting perspective in quantifying the various heads of damages available under this subsection, as well as from a practical legal perspective in commenting on the mechanics of executing the remedy. It will also comment on whether, in these authors’ views, the legal framework of this remedy arrives at a satisfactory result in light of real-world accounting principles and business realities.

In the first section of this article, we set out a conceptual framework for understanding and computing the remedies prescribed under subsection 6(6) of the Act. Subsequent sections explore specific practical issues we have encountered in quantifying these remedies.

The basic concept of rescission

As noted earlier, the Act requires that a franchisor provide a disclosure document containing certain information to a prospective franchisee before that person makes the purchase. The Act provides the franchisee with a statutory right to rescind its “franchise agreement” if it does not receive a disclosure document:

- at least 14 days before the earlier of signing of the franchise agreement, or any other agreement relating to the franchise, and the payment of any consideration relating to the franchise [5];

- as one document, delivered at one time, and delivered in the proper manner [6]; and,

- that contains all “material facts”, financial statements, copies of all agreements proposed to be signed in connection with the franchise, statements as prescribed, and other information as prescribed [7].

Once a franchisee has indicated its desire to exercise its rescission right by delivering a notice of rescission, subsection 6(6) of the Act requires that, within sixty days of the rescission, the franchisor and certain related parties shall:

(a) Refund to the franchisee any money received from or on behalf of the franchisee, other than money for inventory, supplies or equipment;

(b) Purchase from the franchisee any inventory that the franchisee had purchased pursuant to the franchise agreement and remaining at the effective date of rescission, at a price equal to the purchase price paid by the franchisee;

(c) Purchase from the franchisee any supplies and equipment that the franchisee had purchased pursuant to the franchise agreement, at a price equal to the purchase price paid by the franchisee; and

(d) Compensate the franchisee for any losses that the franchisee incurred in acquiring, setting up and operating the franchise, less the amounts set out in clauses (a) to (c) [8].

If the franchisor does not pay these amounts within sixty days, the franchisee may commence an action to recover these amounts and for a declaration that the franchise agreement was properly rescinded.

Though not explicitly stated, the underlying goal of section 6 of the Act is, as has been noted by the Court of Appeal, to be the same as under the rescission remedy at equity, namely:

… to put the franchisee back in its pre-franchise position where there has been non-disclosure, provided notice is served within the prescribed time [9]

This was a sentiment echoed by Justice Murray in one of the few reported cases dealing explicitly with quantification issues under s. 6(6) [10]

The purpose and object of these subsections [i.e. (a) through (d)] of the Arthur Wishart Act are to put the franchisee in the position that it was prior to entering into the franchise agreement.

This objective is accomplished in two parts.

First, the franchisor must, as required by subsections 6(6)(a) through (c), reimburse all money received from the franchisee, and purchase inventory, equipment, and supplies from the franchisee at their original cost to the franchisee. For the most part, these assets represent those specific items that the franchisee needed to buy in order to run the franchise [11].

The Act recognizes that upon rescission, many of the assets originally purchased by the ex-franchisee are now of little value to it. They may be of a specialized nature, being tailored to the franchised business, and therefore highly “illiquid” and impossible to divest at a price anywhere near their original cost. If the franchise business is no longer operating, there is a further issue that this equipment can likely only be sold at bankruptcy or liquidation prices, far below its purchase price. Finally, assets such as leasehold improvements, specialized equipment and inventory, and certainly the “capitalized” [12] portion of the initial franchise fee, are likely of minimal value to an individual who no longer conducts the franchise business. The Act therefore requires the franchisor to purchase or reimburse the franchisee for the value of these items at the price the franchisee paid.

Second, subsection 6(6)(d) of the Act requires the franchisor to compensate the franchisee for any losses incurred in acquiring, setting up and operating the franchise which have not already been captured by subsections 6(6)(a) through (c). Subsection (d) is a broad catch-all designed to capture any other losses which the franchisee may have suffered in connection with the franchise.

If the franchisor pays the amounts under subsection 6(6) of the Act, the theory is that the franchisee will have been restored to its original financial position.

The position of the franchisee

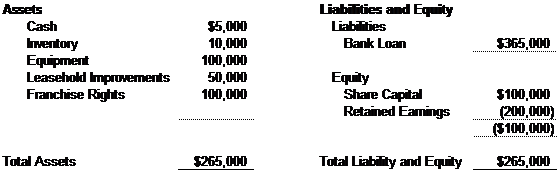

This can be illustrated through a simple example. John Doe purchases a franchise for an initial franchise fee of $100,000, giving him franchise rights in perpetuity. Assume Mr. Doe is not required to make any ongoing royalty or advertising payments to the franchisor. In order to set up the franchise, Mr. Doe purchases $100,000 worth of equipment and $10,000 worth of inventory. He spends $50,000 to renovate his leased premises. Finally, he provides the business with $5,000 as cash on hand in order to fund its daily operations.

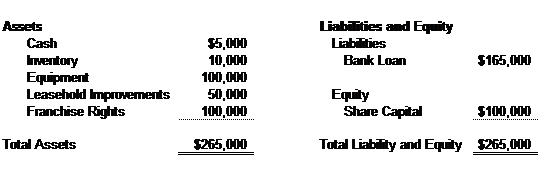

These assets are purchased with $100,000 of Mr. Doe’s own money (i.e. share capital equity) and $165,000 of bank financing. At the beginning of operations, the balance sheet looks as follows:

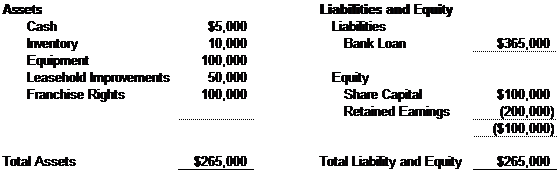

In its first year of operations, the franchise is unsuccessful and suffers operating losses of $200,000. In order to finance these losses, Mr. Doe takes on additional debt of $200,000. At the end of this first year, the owner’s equity section of the balance sheet has decreased from positive $100,000 to negative $100,000, as shown below:

Mr. Doe realizes that the franchise was sold to him on expectations that would be unlikely to be met. He sees a lawyer, who tells him that his disclosure document was materially deficient and that he is entitled to rescind his franchise agreement. He instructs his lawyer to serve a notice of rescission.

Under subsection 6(6) of the Act, Mr. Doe is entitled to $460,000, broken down as follows:

- Reimbursement for franchise fees (s. 6(6)(a)): $100,000;

- Purchase of inventory (s. 6(6)(b)): $10,000;

- Purchase of equipment and leasehold improvements [13] (s. 6(6)(c)): $100,000 + $50,000;

- Reimbursement for operating losses (s. 6(6)(d)): $200,000.

The franchisor pays this amount immediately.

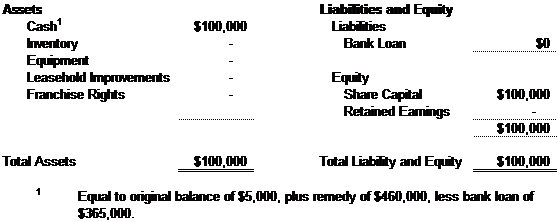

Mr. Doe uses the $460,000 to pay off his bank loan of $365,000, leaving him with $95,000 in excess cash ($460,000 – $365,000 = $95,000). He also transfers all of the business assets to the franchisor, who has purchased them with the payments required under s. 6(6)(b) and (c), with the exception of the $5,000 in cash he had been using to operate his business.

His balance sheet now shows owner’s equity of $100,000, consisting of the $5,000 in his original operating cash as well as the $95,000 left over after having paid off his liabilities:

The $100,000 in cash, unencumbered by any liabilities, is precisely the amount of money Mr. Doe put into the franchise in the first place.

Mr. Doe pays himself a tax-free dividend of $100,000, winds-up the corporation, and walks away from the franchise as though it never existed (except for the late nights and weekend shifts lost in trying to make the business a success). [14]

The position of the franchisor

In the example above, the four paragraphs of subsection 6(6) place the franchisee back in its original financial position. However, what of the franchisor? The franchisor’s obligation to pay for the franchisee’s startup costs under subsection 6(6)(a) results in the franchisor being placed in the same position as the franchisee with respect to these items: the same position it would have been in had the franchisee never purchased the franchise.

However, the other sub-sections are more onerous to the franchisor. The supplies and equipment that the franchisor must purchase from the franchisee at original cost pursuant to subsections 6(6)(b) and (c) are very likely worth nothing near that cost at the time of rescission. Inventory may have spoiled, or may be out of date.

Amounts received from the franchisee may have been used to cover expenses associated with supporting the operation of the rescinding franchisee. For example, a franchisor that collects rent under a sublease agreement might already have remitted it to the landlord.

Yet, while the franchisor retained none of that money, he or she is legally responsible for refunding all of it because of the failure to provide proper disclosure to the franchisee. A franchisor may be considerably worse off as a result of a franchisee’s rescission, making proper and correct disclosure a critical concern.

Analysis of subsections 6(6)(a) through (d)

In the following sections, we outline some of the issues commonly encountered in quantifying the remedy under each subsection of section 6.

Subsection 6(6)(a) – amounts paid to franchisor

Refund to the franchisee any money received from or on behalf of the franchisee, other than money for inventory, supplies or equipment

Items typically claimed under this section include:

- Franchise fees and deposits;

- Royalties;

- Advertising fund payments; and,

- Rent and rent deposits (including those collected by a “franchisor’s associate”) [15].

According to the wording of subsection 6(6)(a), amounts that are owed to the franchisor but have not been paid are not compensable under this section. Expenses accrued for accounting purposes but unpaid should be excluded from subsection 6(6)(a).

Amounts claimed by the franchisee under this subsection should be reconciled against the franchisor’s records to determine if the claimed amounts have actually been paid. Also, the franchisee’s accounts payable ledgers should be examined. They should provide a good summary of what was paid to the franchisor and related companies and what amounts remain unpaid.

Subsection 6(6)(b) – inventory

Purchase from the franchisee any inventory that the franchisee had purchased pursuant to the franchise agreement and remaining at the effective date of rescission, at a price equal to the purchase price paid by the franchisee

The definition of “inventory” is relatively straightforward. The International Accounting Standards define inventory as:

assets held for sale in the ordinary course of business (finished goods), assets in the production process for sale in the ordinary course of business (work in process), and materials and supplies that are consumed in production (raw materials) [16]. This subsection requires the franchisor to purchase the franchisee’s inventory as at the date of rescission for the price the franchisee paid for it.

Inventory counts

Because small businesses do not generally keep detailed, perpetual [17] inventory records, it is prudent for a franchisee who has claimed rescission to perform an inventory count just prior to, or on, the date of rescission [18]. If the amount that will be claimed for inventory is large, the franchisor can be asked to provide a representative to be present during the inventory count, or the franchisee can hire a neutral third party conduct the count and include the cost of doing so to the franchise business.

However, while Courts have held the taking of such inventory counts to be a preferable way of proceeding, they are not essential [19]. Courts have allowed claims for inventory even when only supported by estimates of the remaining inventory, either on the strength of the franchisee’s testimony, or because of evidence as to customary levels of inventory [20]. It is worth remembering that proof in civil legal proceedings need not be perfect, but merely to tip the balance of probabilities.

Offer to return inventory

After conducting an inventory count, a franchisee may wish to make an explicit offer to return the inventory to the franchisor and to advise that, if this offer is not taken up, the franchisee will leave the inventory behind.

Franchisees may initially wish to dispose of the inventory in as cost-effective a manner as possible themselves, and then subtract the revenue generated from the sale from their rescission remedy. While this is, overall, an efficient way to proceed, it exposes the franchisee to risk. It may interfere with the rights of secured parties, or the landlord, to seize those items for their own account, exposing the franchisee to damage claims. Additionally, having the franchisee sell the inventory may allow the franchisor to complain that inventory ought to have garnered more on sale than it did, and to refuse to pay the difference because the inventory is no longer available to be handed over.

The value of perishable inventory is recoverable

Inventory may also be perishable or subject to rapid obsolescence, and may no longer exist by the time a court affirms the franchisee’s rescission claim. However, this does not affect the rescission remedy.

In Springdale [21], the Court ruled that as long as the franchisee offered to return the inventory upon delivery of the notice of rescission, the fact that the inventory had perished by the time the case was decided should not prevent the franchisee from recovering its value.

Subsection 6(6)(c) – supplies and equipment

Purchase from the franchisee any supplies and equipment that the franchisee had purchased pursuant to the franchise agreement, at a price equal to the purchase price paid by the franchisee

What are “supplies” and “equipment”?

As noted above, the intent behind subsection 6(6) is to allow the franchisee to recover from the franchisor the value of “supplies” and “equipment” that are no longer of any use to it now that it has ceased operating the franchised business. Unhelpfully, however, the Act does not define either term.

Interpreted broadly, subsection 6(6)(c) should allow any asset on the franchisee’s balance sheet to be accounted for, as opposed to capturing such amounts as “losses” pursuant to subsection 6(6)(d).

However, it is acknowledged that many assets, such as leasehold improvements, pre-paid expenses, and goodwill, are not typically considered “supplies” or “equipment” as those terms are commonly understood, and while claims for rescission will often include these types of assets in subsection 6(6)(c) of their claims, the jurisprudence dealing with each of these asset classes is not yet well developed.

Leasehold improvements

Leasehold improvements are not normally considered “supplies” or “equipment” from an accounting point of view, even though the example presented earlier assumed that the value of the franchisee’s leasehold improvements was compensable under subsection 6(6)(c) of the Act.

There are very few Canadian franchise cases dealing with whether a franchisee’s outlays on leasehold improvements ought to be seen to be “supplies” or “equipment”, or left to be claimed as subsection 6(6)(d) losses.

In Melnychuk, claims for leasehold improvements were allowed on summary judgement under subsection 6(6)(c), alongside claims for equipment, although without specific comment on this point [22].

The contrary was argued in 2189205 Ontario Inc. et al. v Springdale Pizza Depot Ltd. et al. [23], where the defendant franchisor contested that leasehold improvements were “equipment”. The issue was left undecided in that case because Lederman J. held that the defendants, not having raised the issue until appeal, had left the issue too late in the proceeding to have it fairly decided. The parties had assumed throughout the proceeding that leasehold improvements were “supplies and equipment” that were compensable under subsection 6(6)(c). Justice Lederman mentioned, however, that had the issue been raised in a timely fashion, the plaintiff might have led evidence as to whether leasehold improvements are “equipment”. This suggests that plaintiffs who might benefit from such a characterization may want to adduce such evidence.

A broad view of “supplies” or “equipment” would include leasehold improvements. They are in many ways similar to supplies and equipment: leasehold improvements are often made by the franchisee to particular standards set by the franchisor, in order to maintain the “look and feel” of the franchise system. In many cases the franchisor, or a contractor it hires, actually builds the improvements, which supports the argument that they ought to be treated the same as equipment purchased to run the franchise business and bought back by the franchisor upon rescission.

Even if leasehold improvements are not compensable under subsection 6(6)(c), they would simply be treated as operating losses under subsection 6(6)(d). After all, once the franchisee has walked away from the franchise, such improvements cease to be of any value to the franchisee. For financial accounting purposes, once a franchisee has delivered its notice of rescission, (indicating its intent to rescind the franchise agreement) and left the premises, it would be appropriate to write-down the value of any leasehold improvement assets to nil as the franchisee has arguably lost any ownership claim it had to those improvements.

In most cases it will not make any difference whether these amounts are allocated to subsection 6(6)(c) or (d). The total rescission remedy amount remains the same. The only exception is where the franchisee did not suffer an operating loss and therefore has nothing to claim under subsection 6(6)(d). Springdale confirms that in these cases, amounts from 6(6)(a) through (c) are not to be netted against positive amounts under (d).

Pre-paid expenses and goodwill

“Pre-paid expenses” are amounts that have been paid by the franchisee from which it expects to receive future benefit over a period of time, such as advance payments of rent, utilities and insurance. The franchisee may have allocated a portion of its original purchase price to “goodwill”, which represents the perceived intangible value of the franchise, above and beyond the value of its tangible assets such as inventory, supplies and equipment.

While pre-paid expenses and goodwill items are often reported as assets on a franchisee’s balance sheet, neither typically meets the dictionary definition of either “supplies” or “equipment” [24]. On the other hand, in Melnychuk, the value of goodwill was compensated as part of a subsection 6(6)(c) claim, although without specific comment [25].

Furthermore, when the franchise agreement is rescinded, pre-paid expenses and goodwill, like leasehold improvements, are typically (at least partially) non-refundable and of no value to the franchisee. To the extent that the company suffers a loss as a result, it seems reasonable that a full write-down of these assets would be appropriate, and ought to be recoverable under subsection 6(6)(d) of the Act and not under other subsections.

Condition of supplies and equipment being returned

In Springdale, Master Muir held that a rescinding franchisee must return supplies and equipment to the franchisor and, if it was unwilling to do so, it was not entitled to receive payment from the franchisor for that equipment [26].

However, Master Muir also held that “there is no provision in the Act that requires a rescinding franchisee to make any representations about the quality or condition of the supplies and equipment”, and that any diminution of value of these items was (at least in that case) “a consequence of the decision by the Springdale Defendants to dispute the notice of rescission and their refusal to pay the required compensation” [27] and could not serve to reduce the franchisee’s subsection 6(6)(c) claim.

Although not specifically discussed in Springdale, requiring a franchisee to return supplies and equipment to the franchisor in exchange for payment of the value of those supplies makes economic sense, because:

- To do otherwise would provide the franchisee with a windfall, as he or she would have possession of the supplies and equipment, and would also be receiving their value under the rescission remedy. This is contrary to the general principle, discussed above, that the rescission remedy is designed to put the franchisee back in the place it occupied before entering into the franchise agreement.

- Furthermore, a franchisee who claims rescission is very unlikely to want to continue in a similar business. The franchisee has typically lost a tremendous amount of money and is unlikely to have any use for the particular supplies and equipment. The franchisor, by contrast, is in the best position to re-purpose these supplies and equipment, possibly by selling them to a new franchisee. Insofar as the Act may be used as an instrument to most efficiently re-allocate value and equipment to those who will make best use of them, the franchisee ought to accept payment and give up the supplies and equipment to someone who will use them.

What should the franchisee do with the supplies and equipment?

When making subsection 6(6)(c) claims, a franchisee is often faced with a conundrum. If the franchisor refuses to accept the notice of rescission and pay the required amounts immediately, what is the franchisee to do with its supplies and equipment?

Often franchisees simply leave these items behind. Another option is for the franchisee to move the supplies and equipment to a secure location. However, this may prove impractical and costly. Furthermore, the franchisee may end up returning the supplies and equipment to the franchisor in any event, either because the franchisee no longer has use for them or because of the rationale from the Springdale case. As noted earlier, in Springdale the franchisee had removed supplies and equipment and put them in storage. The Court held that the franchisee had to return them to the franchisor in exchange for subsection 6(6)(c) damages.

The best course appears to be for the franchisee to first offer the supplies and equipment to the franchisor. If the franchisor refuses to deal with them, the franchisee has done all it can and is in the best position possible to be entitled to recover the amounts originally paid. This allows the franchisee to avoid trouble that might arise from taking supplies and equipment from the franchised premises when there might be secured parties or landlords who have claims or rights to that equipment.

“Pursuant to the franchise agreement”

Subsection 6(6)(c) also speaks of “supplies and equipment” that were required to be purchased “pursuant to the franchise agreement”. However, a franchisor may not be required, by the wording of the Act, to pay for any equipment which cannot be demonstrated to have been necessary to the operation of the particular franchised business.

Subsection 6(6)(d)

Compensate the franchisee for any losses that the franchisee incurred in acquiring, setting up and operating the franchise, less the amounts set out in clauses (a) to (c).

This category is a “catch-all” that captures any losses incurred by a franchisee relating to a franchise, minus those already counted in subsections 6(6)(a) through (c), above.

As already noted, if leasehold improvements, goodwill, or prepaid expenses are not recoverable under subsection 6(6)(c), they would no doubt be recoverable under subsection 6(6)(d) as part of the franchisee’s losses.

The following are certain accounting questions that often arise under calculations of losses under subsection 6(6)(d) of the Act.

Owner/manager labor

One issue that arises in almost every case of calculating a franchisee’s operating losses is whether a franchisee can claim the value of his or her labor towards the franchise. This category of damages goes by a number of names, including “owner/manager labor”, “loss of opportunity” [28], or “foregone salary” [29].

It is the authors’ view that the franchisee should be entitled to reasonable compensation in exchange for his or her investment of labor into the business. This labor is a cost of earning revenue, even if it was not recorded on the franchise’s financial statement [30].

The franchisee was required to run the business. Had the franchisee not performed this task, he or she would have had to hire someone else to do so, which would have represented a hard cost to the business.

Furthermore, personal involvement of the franchisee is often a condition of the franchise agreement. It is illogical to allow a franchisor to require this involvement as a condition of granting the franchise, and then not ascribe any value to it if the franchise fails.

While the jurisprudence is still relatively underdeveloped on this point, the idea that franchisee labor is compensable is supported by the little case law that exists, and the authors are unaware of any cases where the value of a franchisee’s labor was held not to be recoverable as a matter of principle.

In Melnychuk v Blitz Ltd. [31], Justice Hockin of the Ontario Superior Court ruled that in addition to the remedy under subsection 6(6) of the Act, which remedy he was willing to grant on summary judgment, the plaintiff might also be able to recover damages related to his loss of opportunity resulting from his having entered into the franchise agreement (i.e. that he could have worked elsewhere and made money at that other endeavor). However, Hockin J. thought that this loss would be a damage claim “at large”, along with mental distress and punitive damages, and was not prepared to dispose of those claims on summary judgment. No conclusive determination as to whether franchisees are entitled to these “loss of opportunity” damages can be drawn from this case.

A similar decision was reached in Grill It Up [32], in which a franchisee quit his job as a casino dealer in expectation of buying a franchise. The franchise purchase fell through. The franchisee was awarded four months of lost income (being $14,692.40) representing his time through to the point at which he ought to have known the purchase was not going to be concluded and ought to have started looking for another job.

Neither of these two decisions describes what subsection of 6(6) this loss of income falls into.

In Springdale [33], the Court considered a claim for loss of wages under subsection 6(6)(d), and granted damages for this loss of $40,000. Although the plaintiffs sought a higher amount based on the amounts recorded in their personal tax returns from the period prior to opening the franchise, the Court noted that these amounts were not corroborated by the plaintiffs’ Notices of Assessment issued to them by the Canada Revenue Agency

Cost of invested capital

A similar analysis can be applied to the issue of the cost of capital. When the franchisee borrows funds from a financial institution and incurs interest expenses, it is clear that such expenses should be deducted in the computation of “operating losses” under subsection 6(6)(d).

But what if the franchise assets were financed with a shareholder loan, with interest paid to the personal franchisee/shareholder? Indeed, what if the assets of the franchise were financed with equity and no interest was charged at all by the person putting up the equity? Should the cost of financing the franchise’s assets during the period of operation be deducted as part of the calculation of “operating losses”?

Finance theory would argue that regardless of how the franchise’s financing is recorded on the income statement, there is a cost associated with having funds tied up in an investment for a period of time. This cost consists of both the “time value of money”, which is the cost of not having access to one’s capital for a period of time, as well as a level of compensation for the riskiness of the investment to which the capital has been allocated. To the extent that this amount is not recorded on the financial statement, it should be imputed [34]

This issue arose in Grill It Up [35], in which the franchisee had claimed 8% interest on a loan given to him by his sister. The judge disallowed the claim, finding that the general compensation for loss of use of money – prejudgment interest granted on the damages total in accordance with the Ontario Courts of Justice Act [36] – would satisfactorily compensate the franchisee for the loss of the use of this money. However, this case might have been decided on its evidence. The Court also noted that better evidence might have been adduced of actual repayment of this loan, as well as interest rate costs on other monies borrowed by the franchisee.

The importance of categorization

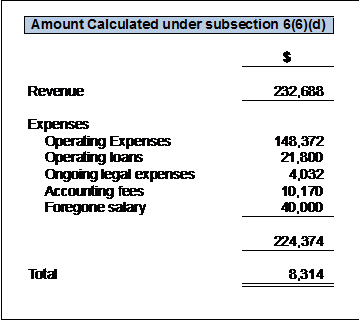

In the recent Springdale case, the Court was faced with the following issue. After calculating losses under subsections 6(6)(a), (b) and (c), the Court found, after it considered all amounts relevant to subsection 6(6)(d), that the franchisee had actually made a small profit, as shown below:

The Court was faced with the question of whether this gain under subsection 6(6)(d) ought to be offset against the losses calculated under subsections 6(6)(a) through (c).

The Springdale Defendants seemed to suggest in argument that the compensation owing to the plaintiffs under sections 6(6)(a), (b) and (c) of the Act should be set-off against the gross revenue calculated in accordance with section 6(6)(d) of the Act. I do not accept this argument. The expense/revenue calculations made under section 6(6)(d) specifically exclude any of the expense items set out in sections 6(6)(a), (b) and (c) of the Act. The same argument was advanced by the defendant in Payne Environmental and found to be untenable by Justice Murray. See Payne Environmental at paragraph 12. I agree with Justice Murray. As long as the sections 6(6)(a), (b) and (c) amounts are not included in the calculation of the franchisee’s expenses under section 6(6)(d), no deduction need be made [37].

While this may be an interpretation consistent with the wording of the Act, it highlights the tension between that wording and the intent of the Act: to place the franchisee back in its pre-franchise position [38]. The result of Springdale is that it placed the franchisees in a better financial position than they had been in prior to purchasing the franchise [39].

To consider the potential consequences of the Springdale reasoning which treats each subsection as an independent head of compensation, consider the following example of two franchise systems. The two systems are identical, but for the following differences:

- Under system ABC, franchisees pay their rent directly to their landlord; under system XYZ, the franchisor subleases the location.

- Under system ABC, franchisees pay a 10% royalty on purchases of inventory, which they buy from the franchisor; under system XYZ, franchisees pay a 5% royalty on all sales.

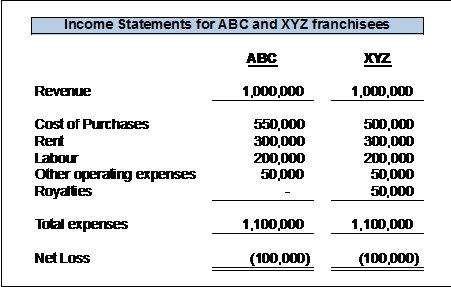

Both businesses operate for 1 year, making $1M in sales and incurring $1,100,000 in expenses, as shown below:

At the end of their single year of operations, both franchisees have no inventory left on hand; conveniently for the sake of our example, both franchisees also managed to sell off all of their remaining supplies and equipment.

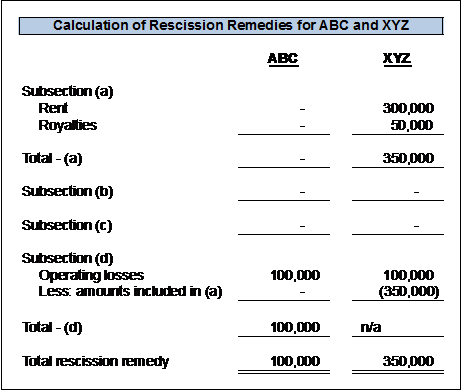

The table above shows the rescission remedy for each franchisee. ABC’s calculation is fairly simple. ABC has not paid any royalties to the franchisor other than for inventory; its rent is paid directly to its landlord. ABC suffered an operating loss of $100,000. It therefore claims $100,000 under subsection (d), thereby placing itself back in the same financial position it was in prior to acquiring the franchise.

XYZ, on the other hand, has paid $300,000 in rent to the franchisor on its sublease. It has also paid royalties of $50,000; therefore, it collects $350,000 under subsection (a). As with ABC, no inventory, supplies or equipment remain. Under subsection (d), we start with XYZ’s operating loss of $100,000. However, once we deduct amounts already included under subsection (a), there is no longer any loss. Abandoning any claim under subsection (d), XYZ walks away with a rescission remedy of $350,000, in spite of having lost only $100,000. XYZ appears to have received a windfall of $250,000.

This is an extreme example. However, it illustrates how subsections 6(6)(a) through (d) are interconnected; they are not four separate heads of damage, but an integrated formula that should return the franchisee to its original financial position.

Common errors in making rescission claims

There are a number of errors we have encountered in our assessment of claims made by rescinding franchisees under the Act. Most of these errors involve double-counting amounts under the different clauses of subsection 6(6) of the Act, including:

- Claiming royalties paid to the franchisor subsection 6(6)(a), and also including these amounts as operating expenses as part of the computation of operating losses under subsection 6(6)(d);

- Claiming the original, un-depreciated cost of equipment under subsection 6(6)(c), and also including depreciation on this equipment as part of the calculation of operating losses under subsection 6(6)(d);

- Claiming the original, un-amortized cost of the franchise rights under subsection 6(6)(a), and yet including depreciation on these intangible assets as part of the calculation of operating losses under subsection 6(6)(d);

- Claiming the value of liabilities (shareholder loans, bank loans), and yet also claiming the operating losses that gave rise to those liabilities as well. In the example above, compensating Mr. Doe for the $365,000 in liabilities incurred in setting up and running his franchise, as well as for the $200,000 in operating losses, would have resulted in a windfall of $105,000.

Events subsequent to the rescission

Loss of opportunity (cost of capital) after rescission

The mechanics of the Act require the franchisor, in response to a franchisee delivering a notice of rescission, to issue payment of the sums laid out in subsection 6(6) the Act to the franchisee within 60 days. This is almost never what the franchisor does. However, the franchisee is thereby precluded, from the 60th day after the date of rescission onwards, from using the money which the Act requires to be reimbursed to it, to invest in alternate business opportunities.

The question becomes how should this additional loss be compensated? In some ways, this loss of opportunity (of capital) is similar to that already discussed under “Cost of Invested Capital”, above, except that this loss post-dates rescission.

One view, as discussed under that heading earlier in this paper, is that the statutory pre-judgment interest rates mandated by the Ontario Courts of Justice Act adequately compensates the franchisee for this loss. It may be argued, however, that these statutory pre-judgment interest rates, which reflect rates of return on risk-free investments, may not reflect the risks or returns that the franchisee would have incurred and earned had they had access to the proceeds of rescission in a timely manner. As was stated in one P.E.I. Supreme Court Trial Division case,

[Pre-judgment interest] is an appropriate statutory recognition that for everyone in business there is a cost of capital. Where payment is not made on time, the debtor is unjustly enriched and the creditor is denied the opportunity cost of that money. It is fitting that a creditor should not be required to demonstrate direct loss through bank or other creditor indebtedness. The statutory scheme expressly entitles the creditor to claim and have included prejudgment interest as an integral part of the judgment [40].

Courts also have discretion to increase the pre-judgment interest rates beyond that specified by the Courts of Justice Act by way of expectation damages or restitutionary damages. A franchisee might rely upon this discretion to properly compensate it for the loss of its capital [41].

This imports common law arguments, and a reliance on a broad judicial power, into a rescission analysis, which may not be desirable in connection with a statutory damages scheme.

A further, alternate, view would include these lost opportunity costs as additional subsection 6(6)(d) damages that should be claimed by franchisees. This final view has the benefit of maintaining the scheme of the Act, but leaves the parties to determine how to quantify the loss of opportunity [42].

None of these views has to date been endorsed in franchise jurisprudence dealing with the Act [43]. This is an unsettled area of the law, as well as in the financial field [44].

Settlement of liabilities

Another issue that is not directly dealt with by the Act is how to deal with liabilities which the franchisee manages to reduce in value or extinguish at some point after delivering its notice of rescission. The Act speaks of a franchisor refunding and purchasing from the franchisee those subsection 6(6) damage items within 60 days of the effective date of rescission [45]. However, what of events subsequent to the date of rescission? Are they to be considered in an assessment of rescission damages?

For example, small business loans typically require a personal guarantee of only 25% of the principal. In some instances, the plaintiff franchisee corporation may already have defaulted on a significant portion of its debt obligations. In a perfect world, the franchisor would reimburse the franchisee the value of this small business loan, and the franchisee would then use these funds to pay the bank.

Given that the basic concept of subsection 6(6) of the Act is to substantially restore the franchisee to its original financial position at the date of acquisition, it might be unfair to require the franchisor to pay the full amounts calculated under subsections 6(6)(a) through (d) without crediting it for any reduction in the franchisee’s debt or any amount not otherwise payable by the franchisee. To do otherwise would be to provide the franchisee with a windfall, as illustrated below.

Returning to the example with which we opened this article (Example #1), assume that of the original $165,000 in bank debt, 25%, or $41,250, was guaranteed personally by the shareholder and the remaining $123,750 was secured only by corporate assets. As before, the balance sheet following Year 1 was as follows:

Assume that Mr. Doe walks away from the restaurant upon rescission, and that he eventually settles the original outstanding bank loan for $40,000.

A strong argument can be made that in this case, Mr. Doe’s entitlement under subsection 6(6) is significantly lower than the $460,000 calculated above. Mr. Doe has received a “gain” on the write-down of his company’s bank loan of $125,000. Mr. Doe requires only $335,000 (that is, $460,000 less the $125,000 write-down) in order to return the company to its original financial position. Were Mr. Doe to receive the $460,000 as calculated under the Act, he would receive a windfall.

Proving damages

We have described the mechanism of rescission in the Act, and some of the issues arising from the matching of subsections 6(a) through (d) of the Act with the practical realities of the exercise of rescission. However, proof of the value of the rescission remedy that ought to be awarded, and how one quantifies it, are separate matters.

We therefore present in this section our thoughts on documents that ought to be investigated to pin down the value of a rescission claim, as well as two methods for quickly estimating the value of a rescission claim so as to tailor the scope and size of a legal and accounting response to the size of the case at hand.

Information to request

While every franchise rescission case is different, there are a number of common documents that counsel may wish to consider obtaining from the franchisee early on in any engagement.

These documents should allow counsel to arrive at a preliminary sense of the potential magnitude of the claim, which will greatly aid in useful settlement discussions or in keeping litigation strategy appropriately tailored to the size of the case.

Subsection 6(6)(a)

- Offers including amounts to be paid by the prospective franchisee for the franchise;

- Franchise business plan, if it contains costs;

- Franchise agreement;

- Sublease agreement;

- Agreements of Purchase and Sale with the franchisor (if any);

- Cancelled cheques and/or bank statements relating to the payment of the initial franchise fee and any deposits or other money paid to the franchisor.

- Cancelled cheques and/or bank statements reflecting ongoing royalties/advertising fund payments (alternately these may be obtained from the accounts payable ledger);

Subsection 6(6)(b)

- Inventory count sheets from the date of rescission (or a recent date);

- Sales and purchases ledgers;

Subsection 6(6)(c)

- Copies of all invoices and cancelled cheques/proof of payment relating to the acquisition of supplies and equipment;

- Copies of all construction contracts;

Subsection 6(6)(d)

- Annual financial statements, as well as the underlying general ledgers and trial balances;

- Monthly/weekly revenue reports submitted to the franchisor;

- Corporate tax returns;

- Personal tax returns for the owners of the franchise for the period from two years prior to entering into the franchise agreement to the current date;

- T4 slips issued to all employees;

Of course, in examining original source documents a balance must be struck between looking at every source document and the costs that would be incurred in so doing.

It is prudent for source documents to be requested for all material items. This may include invoices and contracts relating to the initial purchase of the franchise, and any capital assets, loan agreements, T4 summaries and (sometimes) the periodic sales reports prepared for the franchisor, for example.

However, because it is generally not economical to vouch every expense item to an original receipt or invoice, for the remaining non-material items, the franchisee’s income statement can simply be tested for its overall reasonableness and source documents obtained sufficient to allow this testing.

Initial assessment of subsection 6(6)(d) losses

Franchisees may not have kept pristine operating records, and this can make calculating the rescission remedy, and in particular the subsection 6(6)(d) component of it, quite difficult. While franchisees may feel differently, losses under subsection (d) are not in all cases significant sums of money, and a full re-construction of the franchisee’s losses from these imperfect financial records may prove prohibitive.

Two accounting techniques that may assist in quickly estimating these subsection 6(6)(d) losses are presented below. They may assist in determining at the outset of a case whether a more fulsome examination of these damages is warranted, and if anything appears on a very rough first glance to be out of line for the business at issue.

If justified as a result of these quick techniques, a more thorough examination of the franchisee’s records and receipts can then be undertaken.

Labor cost estimates

Consider a franchisee that operated a relatively large franchise restaurant, reporting sales of $1,000,000. Assume also that the franchisee paid his or her employees in cash.

Industry statistics show that labor costs for larger restaurants are typically equal to 25% to 35% of sales, so one can estimate that total labor costs for this restaurant should have been approximately $250,000 to $350,000 [46].

Based on this, one simple question for counsel to consider at the outset of any rescission claim is whether it is possible (or likely) that this particular franchisee lost in excess of $250,000. If not, the franchisee may find it difficult to recover any amounts under subsection 6(6)(d) because the $250,000 to $300,000 in expenses which cannot be proven may make the franchise appear more profitable than it in fact was. This is a simple exercise that, if undertaken at the outset of a dispute, can save the litigants time and money.

Detection of unreported income

Suppose that the franchisee has provided relative complete records with respect to its expenses, which appear to exceed reported revenues by a significant amount. Unfortunately, this may be only half the battle.

Consider the example of a franchisee that operated a restaurant. It presents financial statements showing revenue of $400,000, cost of sales (i.e. food and drink) of $190,000, and other operating expenses (rent, professional fees, etc.) of $320,000, for total operating losses of $110,000.

In examining the revenue figure, however, we ought to consider that the average cost of sales for a full-service restaurant will generally be in the range of 35%. Yet this franchisee shows a much higher cost of sales, of approximately 48%. While some allowance may need to be made to account for poor management skills, this accounting ratio may be evidence that there have been some unreported cash sales. (See the Springdale appeal [47] case, where this issue arose).

Conclusion

The statutory rescission remedy outlined in the Act differs significantly from the rescission remedy that has always been available at equity. Unlike rescission at equity, which seeks to return both parties to the status quo ante, the Act’s subsection 6(6) remedy will generally result in the franchisor being worse off. Moreover, at least based on the current state of the jurisprudence, and the current wording of the Act, the rescinding franchisee may on occasion end up in a better position that when it purchased the franchise.

Nonetheless, this paper has argued that the basic premise of the Act is that it seeks to return the franchisee to its original financial position at the time of the franchise’s opening. While there are doubtless many other matters of law and accounting that have yet to be determined in the jurisprudence, in these authors’ view once the basic principles underpinning subsection 6(6) are properly understood both franchisees and franchisors can use the spirit and intent behind this section to arrive at a proper quantification of compensation to put the franchisee back in the position it ought to be in.

In particular, we argue that the categories outlined in subsections 6(6)(a) through (d) should be interpreted in an integrative fashion; the types of categorization “shell games” that are implied by the recent Springdale decision (see above, Section 4 for an admittedly extreme example), are contrary to the principle behind the Act. These categories should be interpreted inclusively, and ought to fully and completely indemnify the franchisee for all its losses. To accomplish this, franchisees ought to claim, and franchisors ought to be obliged to pay, items that are not yet typical in the jurisprudence including claims for owner/manager labor, the cost of capital, and consequential lost profits in the event that the franchisee is unable to pursue other business ventures.

The Arthur Wishart Act has generated significant volumes of litigation in its brief lifetime; yet many points of interpretation remain unaddressed in the jurisprudence. It is our hope that the theoretical and practical points set out in this article will contribute to filling some of these gaps.

By: Ephraim Stulberg and Jonathan Mesiano-Crookston, partner of Goldman Hine LLP.

The statements or comments contained within this article are based on the author’s own knowledge and experience and do not necessarily represent those of the firm, other partners, our clients, or other business partners.

Ephraim Stulberg

Ephraim Stulberg